As we covered in the previous section, public blockchains depend on a network of nodes to maintain the system and store all of the pertinent data.

In the event that a single actor is able to take control of more than 50% of the nodes, it is possible for them to update the history of the chain with new records. This presents a substantial vulnerability for systems such as Bitcoin, in which there is a large amount of wealth available to anyone who can compromise the network.

While it is possible for a bad actor to overtake a network, this does not mean that the network must accept the new version of the blockchain as proposed by the bad actor. In fact, a 51% attack is generally so expensive to maintain that efforts are short lived when they do occur. In the event of a 51% attack, the bad actor would need to not only maintain a majority of the network’s hashing power, but they would also need to somehow convince the other nodes that they should adopt new information while disregarding their existing record of the network.

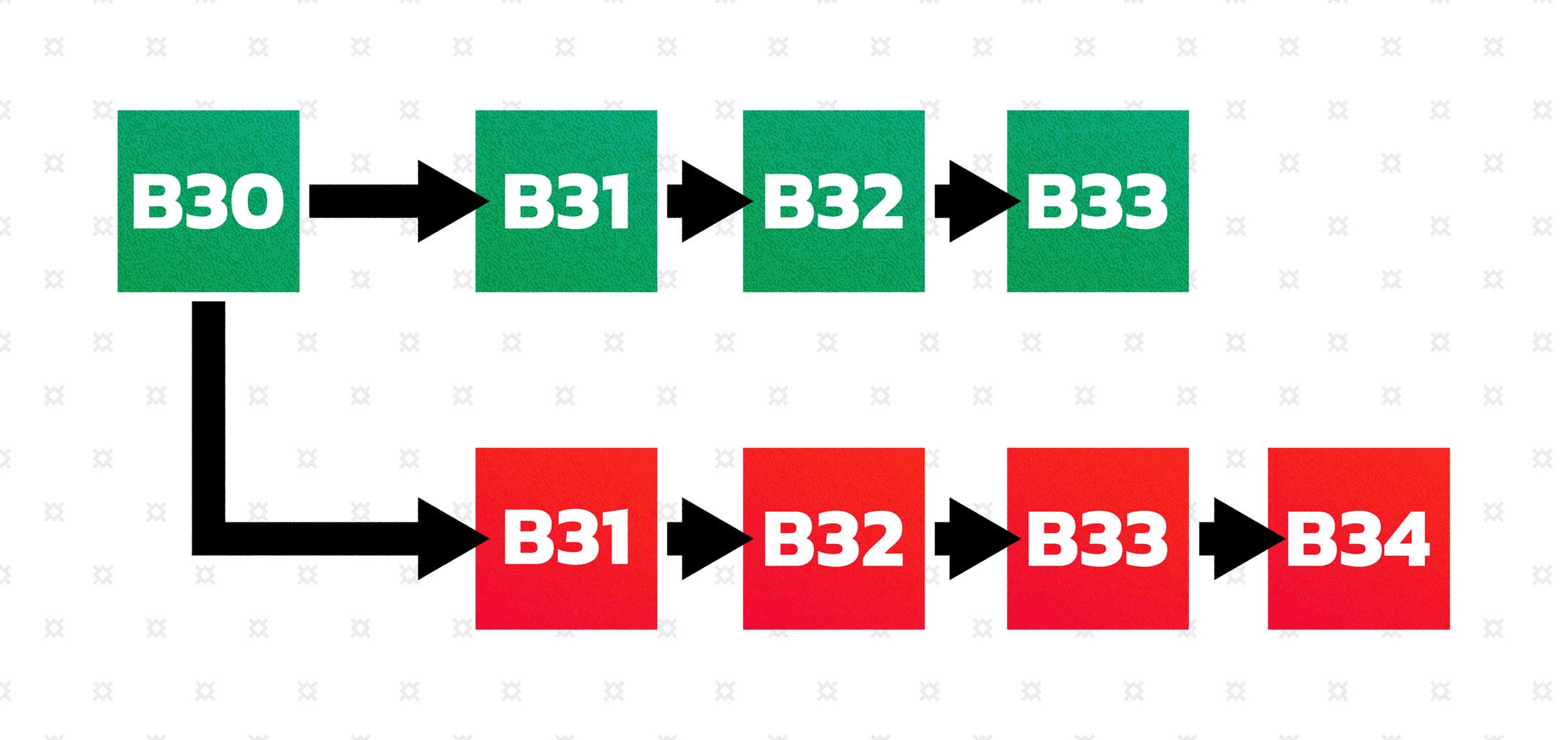

51% Attack

In a 51% attack, a malicious actor takes over a majority of the network's nodes, which allows them to propose and confirm transactions without the need for approval from anyone else in the network.An analogy may help to further consider this scenario. Suppose that some troublemaker is trying to change a historical article on Wikipedia. Once the malicious actor finds out how to bypass basic moderation, they will be able to rewrite history as they see fit, however, Wikipedia’s administrators will likely work to redefine the system to ensure that malicious actors only have a short time to make these changes. However, as long as a record exists of the true state of the system, it is possible to revert the changes made by the malicious party and exclude them from the new network.